No products in the cart.

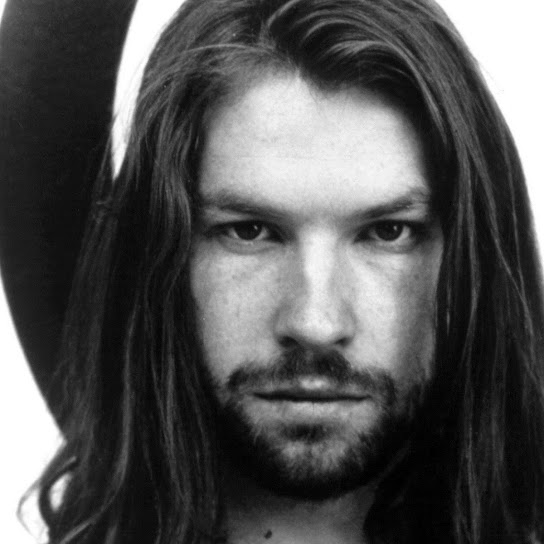

Aphex Twin vs Taylor Swift, or when the underground wins… without meaning to

Aphex Twin recently surpassed Taylor Swift in monthly listeners on YouTube. The news surprised, amused, and sometimes fascinated people. How can a historic figure of experimental electronic music—largely media-shy and far removed from contemporary promotional logics—outpace one of the world’s biggest pop stars on such a massive platform?

The answer lies less in a sudden shift in taste than in the way platforms measure, aggregate, and transform music listening.

According to data shared by DJ and analyst RamonPang, Aphex Twin reaches around 448 million monthly listeners on YouTube, compared to 399 million for Taylor Swift. A significant gap—but a misleading one if read as a classic indicator of popularity. YouTube doesn’t just count intentional listens. The platform also aggregates passive usage, Shorts, videos that reuse a track as background sound, and content reposted from TikTok or Instagram.

In reality, Aphex Twin’s “active” audience on YouTube Music is closer to 5 million listeners. Still impressive for an artist from that sphere, but nowhere near the global figures being displayed. What these hundreds of millions actually measure, then, is not attentive listening, but omnipresence.

At the heart of this phenomenon lies QKThr, a track taken from Drukqs, an album released in 2001. Twenty-five years later, the track has become a viral sound, used in millions of videos on TikTok and YouTube Shorts. It appears in so-called “corecore” edits, absurd memes, “subtle foreshadowing” videos, hopecore, or post-internet edits. QKThr is no longer listened to for itself; it is mobilized as sonic background.

What does it even mean to “listen” to music today? In this context, Aphex Twin is not being rediscovered as an artist, nor even as the author of a specific album. He becomes a cultural resource—a reusable material, cut up, repurposed, and stripped of its original context. His music works because it is abstract enough to adapt to any visual narrative, recognizable enough to produce an effect, yet blurred enough not to impose meaning.

Resident Advisor even raises a hypothesis: will Generation Z and Alpha feel nostalgic for QKThr in a few decades, without ever having known its era, its context, or even the album it came from? A nostalgia without memory, produced by the algorithm rather than by cultural transmission.

Comparing Aphex Twin and Taylor Swift through these figures ultimately means comparing two radically different uses of music, flattened by the same measurement tool. On YouTube, a pop ballad, a twenty-year-old IDM track, a podcast, or a recycled short clip are all counted according to the same logic. The platform does not hierarchize meaning; it aggregates fragments of attention.

Within this framework, Aphex Twin’s “achievement” says nothing about an underground victory over pop. It mainly reveals the platforms’ ability to absorb all aesthetics—even the most radical ones—and turn them into exploitable flows. Aphex Twin hasn’t changed his music. The system, however, has changed the way that music circulates, is used, and is counted.

So the question is not who wins between Aphex Twin and Taylor Swift. The real question lies elsewhere: what do these numbers actually measure? And when did we accept algorithmic visibility as a substitute for listening as the main indicator of musical value?

Tagged with :