No products in the cart.

Do you really have to live in Paris to matter in electronic music?

Of the 24 DJs interviewed for this Clubbing TV investigation, 100% live outside the capital. Amiens, Montpellier, Lyon, Bordeaux, Nantes, Rennes, Limoges, Toulouse, Brussels, a village in the Drôme, Haute-Savoie… The French electronic music scene, as it is told here, is being built largely beyond the périphérique. And it is precisely this gap—between a fantasised centrality and very concrete local realities—that runs through all of the testimonies.

This corpus is neither a representative survey nor a manifesto. It is a snapshot. Twenty-four trajectories, twenty-four ways of making a musical project exist outside Paris. Among them, twelve women and/or non-binary people—an element that directly shapes how issues of networking, legitimacy, visibility, and outreach are discussed.

A very concrete geography

Certain cities come up repeatedly. Amiens alone accounts for seven testimonies (thanks to tentakeur). It crystallises tensions common to many local scenes: the absence of dedicated clubs, programming concentrated in bars, reliance on collectives, economic fragility. But also solidarity, resourcefulness, informal initiatives, and the creation of alternative spaces where none previously existed.

At the other end of the spectrum, regional metropolises such as Lyon, Bordeaux, Toulouse, or Montpellier appear as paradoxical zones. On paper, they offer more opportunities, more venues, larger audiences. In reality, they also concentrate more competition, sometimes rigid formats, and an expected level of professionalisation that is not always accessible. A structured ecosystem often collides with a reality far more inflexible than anticipated.

Finally, some testimonies come from territories rarely mentioned in media narratives: Limoges, Haute-Savoie, the countryside, deep rural areas. They remind us that for many artists, the issue is not about breaking through or scaling up, but simply about playing, meeting an audience, and making a scene exist where it is almost nonexistent.

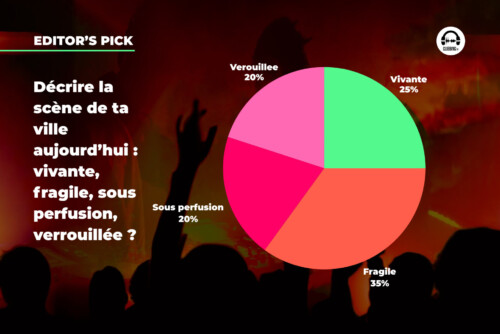

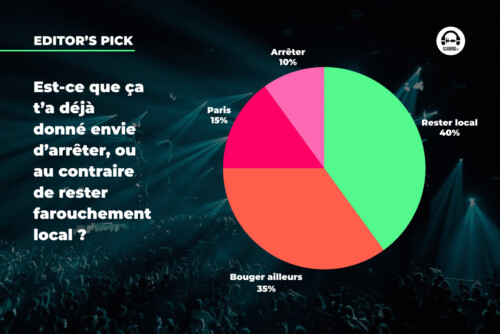

Holding on, adapting, continuing

Contrary to the dominant narrative of a fragile or discouraged scene outside Paris, what these trajectories mostly reveal is a strong capacity for adaptation. 8 out of 10 artists have never felt like quitting. They adjust their formats, their expectations, their modes of distribution. 42% choose to strengthen their local scene rather than leave.

As Kirara puts it:

Yes, clearly. It made me want to stay fiercely local in Lyon. The idea of starting from scratch in Paris—having to rebuild a reputation, connections with bookers, organisers, and the audience—really puts me off. Today, being based in Lyon genuinely contributes to my well-being.

Only 21% mention a real temptation to give up.

Bo Meng: It has already made me want to stop because it’s discouraging. But the love for my local scene—the one that once made me dream of being on stage—remains stronger.

The majority do not dream of Paris. They invent parallel trajectories—often slower, sometimes more precarious, but also more consistent with their values, their mental health, and their everyday reality.

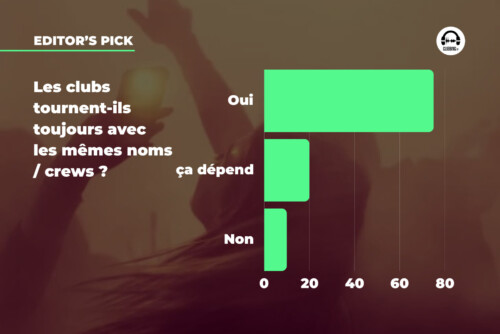

Do clubs really give artists opportunities — or always the same names?

Nearly two-thirds of respondents believe that line-ups often circulate within a closed loop, with the same artists or collectives regularly rebooked. But the testimonies strongly nuance the idea of simple nepotism. Many point first and foremost to economic realities. Organising a party is expensive. Margins are thin. Rebooking already identified names is often perceived as less risky.

Residencies, habitual programming practices, and pressure to remain profitable thus create a form of sometimes unintentional lock-in. Conversely, several artists highlight that alternative, non-profit, or informal scenes remain today the main spaces where artistic diversity can truly be expressed. Where these spaces exist, turnover is higher and aesthetics more varied. The issue, then, is not inevitability but one of structures, resources, and local political choices.

For a Lyon-based DJ who wished to remain anonymous, the assessment is bitter. Le Sucre, which he nevertheless describes as his favourite club and one of the most politically engaged, sees—according to him—the same names returning month after month, both among established and emerging artists. He perceives a contradiction between the publicly stated commitment to diversity and a programming strategy that struggles to genuinely uncover new talent, leaving certain aesthetics durably invisible.

Tentakeur, based in Amiens, clearly distinguishes between contexts. Yes, in bars, where the same profiles close to venue owners often reappear. Yes, in certain warehouse parties organised by closed circles that book their own networks around a few headliners. But no, in informal venues, associations, and squats, where programming is genuinely diverse and allows new artists to be discovered every month.

Conversely, Tetris Owl believes that many new artists emerge precisely because they are cheaper. In a context where organising events is increasingly costly, local beginner DJs become a preferred economic solution.

BETÏSES further nuances the picture by comparing Nantes and Lyon. In Nantes, clubs work with numerous local collectives and rotation is real. In Lyon, she observes instead a dominance of self-produced events and a handful of recurring collectives, which significantly hampers local emergence.

For Yerz, it is also a matter of lack of eclecticism:

Opportunities are rare, and local institutions neglect techno and electronic music. You have to carve out your own space, but there are very few legitimate, safe, and artistically interesting venues to offer anything other than hard techno or commercial house.

How do you survive artistically when you’re not part of the “right circles”?

For many, surviving artistically outside the “right circles” begins with a fundamental reminder of the very meaning of the process itself. “By never forgetting why you do this”, explains Tetris Owl, adding that “when you’re aligned with yourself, everything you hope to have one day doesn’t weigh much against what you once dreamed of having — and already have today”. A way of saying that survival first comes through personal alignment, before any career strategy.

“You survive within a microcosm”, sums up LACRIZOMIKE 2000, “I feel that your surroundings and your network are essential in order to grow”. Even for those who do not feel completely excluded from dominant circles, the difficulty remains very real: “even within the right circles, surviving artistically is complicated”, Colleg tells us. The issue is not only access, but also geography, favouritism, and career logics — particularly Paris-centric ones.

Far from power networks, survival often happens within microcosms — local or affinity-based scenes where one’s immediate circle is vital. “You need to be in a circle that shares your values”, explains Kirara, who openly admits that without these queer, bass-driven, local, or activist circles, “I would clearly be floundering”.

In response, several answers describe survival as a mix of resourcefulness, outreach, and persistence: “making contacts, reaching out, DARING”, “we do the best we can”, or “a lot of outreach, talent contests”. Some also openly acknowledge a form of long-term precarity: “we work on the side”, Axy_D tells us somewhat bitterly, while Scorch confirms: “artistically, if DJing and production are your main activities, I think it’s over”.

Others choose to build elsewhere — more slowly, but differently. “There’s so much to do in the South, despite an exhausted scene”, says Cabale, stressing the importance of “sticking together, forming a collective body instead of tearing each other down”. For Ginger808, survival means creating new circles: “the idea was to create new circles, with friends who became collaborators”.

Finally, several testimonies offer a more direct critique of the system itself. “It all depends on what we mean by ‘the right circles’”, writes Tentakeur, reminding us that “those under the spotlight often end up questioning their values and integrity”, and stating clearly: “you survive just fine without them — and you lose fewer hit points”. A survival that is less visible, less validated, but sometimes more sincere — even if, as one final testimony reminds us, “surviving artistically when you’re not in the right circles is really hard”.

At some point, were you made to feel that the “real next step” meant Paris?

For many of the artists interviewed, the idea that the next step necessarily goes through Paris remains deeply ingrained. Nearly 70% say that at some point, they were made to understand that moving to the capital was a necessary step. Sometimes explicitly. More often in a diffuse way—through remarks, conditional opportunities, or an implicit collective pressure.

Around a quarter of respondents take a more nuanced position. It would depend on musical style, career stage, or the way one envisions the development of their project. 16% say they have never felt this injunction, often because they operate within scenes already structured elsewhere or in genres less dependent on Parisian centrality.

What clearly emerges is that Paris functions less as a formal obligation than as a symbolic horizon of success. An idea that circulates among peers, through well-meaning advice and trajectory comparisons. Yet several artists who tried the experience describe a more mixed—sometimes disappointing—reality. Saturated scenes, precarity, a fantasy stronger than what the capital actually offers.

Shanixx, based in Bordeaux, explains that she never felt this necessity. Just two hours by train from Paris, she was able to build strong connections with the Parisian scene while maintaining a living environment conducive to production and the preservation of her mental health.

DJ Koyla, on the other hand, says she moved to Paris very early, before eventually returning to Bordeaux. It was there that her project truly took off, showing that development outside the capital is possible—even if Paris often remains a point of passage.

Solitary Shell, from the Lyon psytrance scene, never felt this pressure either, reminding us that some genres thrive perfectly well outside Paris.

Have you ever felt looked down on because you came from another city?

The issue of contempt or condescension divides respondents more sharply. Slightly more than half say they have never experienced any explicit condescending attitude linked to their geographical origin. For them, the scene remains generally open within the context of parties and collaborations.

But this assessment is largely tempered by more ambiguous accounts. Around a third describe a contempt that is never outright, but very real. Residencies perceived as less prestigious, gigs considered less important than those of Paris-based artists, difficulties accessing media, radio, or certain institutions. Distance then becomes a kind of invisible filter weighing on recognition.

Finally, a minority recounts openly expressed contempt, sometimes stated without restraint. References to “provincials,” clichés about mid-sized cities, the exoticisation of rural areas. Colleg, who lives in the Drôme, evokes the feeling that his gigs would count for less—and the almost caricatural surprise at the idea that someone could come from the countryside and still have a strong musical culture.

And then there’s this answer that genuinely made us laugh: Axy_D:

When I was in Berlin, yes. Not in Paris—who do they think they’re looking down on with their packed metros and €14 pints, taxes included, lmao.

Has where you live ever mattered more than the music itself?

To this question, the majority answer yes—or rather yes. 46% say they have felt that their location weighed more heavily than their music, especially at the beginning. Difficulty accessing opportunities, the rarity of warm-up slots, the impossibility of turning an initial booking into continuity without being physically present in certain networks.

A third adopt a more nuanced position. Music remains central, but geography influences the speed of progression, visibility, and access to scenes. It acts as a silent filter—logistical, economic, and mental.

Finally, 21% believe that where they live has never mattered more than their music. Some explain that their audience simply did not know where they were based. Others feel that their style resonated more elsewhere than in Paris.

Local scenes: spaces of freedom, or freedom under constraint?

When asked whether local scenes now offer spaces of freedom that Paris may have partly lost, the responses paint a nuanced picture. For Lacrizomike 2000, the difference is largely one of scale. In more intimate cities like Grenoble, he feels a sense of freshness, passion, and goodwill—particularly within non-profit, community-based scenes.

Cabale observes that innovation and risk-taking are now more present in cities like Marseille or Montpellier, where one has to convince a less exposed audience and offer something new, far from formatted shows.

Kirara tempers this view, noting that in Lyon, the lack of venues, the weight of large organisations, and the cost of partying sometimes stifle freedom—while Paris paradoxically still retains more genuinely underground spaces.

For Tentakeur, local scenes above all respond to a vital need for community. In Amiens, certain initiatives exist simply because bonds must be created where almost nothing exists. Ginger 808 reminds us that regional programmers are often more cautious, constrained by profitability and a lack of infrastructure. Freedom exists—but it often collides with a logic of entertainment.

Mysterykid raises an interesting point about fees:

With the sheer number of DJs today and line-ups endlessly rotating in Paris, local scenes are a real blessing for anyone who needs to earn their fees.

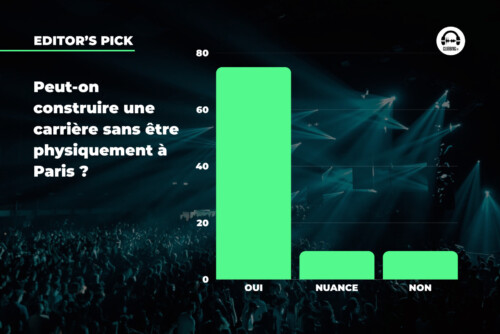

Do you think it’s possible today to build a career without being there physically?

A large share of testimonies say yes—it is possible, but rarely simple, and almost never linear. Social media, the internet, and increased artist mobility now make it possible to secure gigs, gain visibility, or collaborate remotely without necessarily living in the capital. That said, many stress that Paris remains a central platform: a place for encounters, collaborations, access to media, labels, and agencies—where “everyone is there.”

Several mention the option of going there occasionally, without living there, as a more sustainable form of balance. But this flexibility comes at a cost: long journeys, transport and accommodation expenses often borne by artists, reduced fees, exclusivity clauses that are harder to maintain when based elsewhere (Cabale), and a recurring feeling of unequal treatment for those coming from outside.

Behind the appealing idea of a decentralised career, some point out that depending on the scene, the formats, and one’s ambitions, financial autonomy remains very difficult to achieve outside major centres—especially for artists aiming at clubs, warehouses, or established festivals. Conversely, other trajectories—more collective, more local, or rooted in alternative scenes—show that there are different ways of “succeeding,” sometimes by accepting that music will not be the sole source of income.

Behind the injunction to “move closer to Paris,” an implicit norm emerges: being validated by certain structures without benefiting from the same conditions as local artists. A centralisation that doesn’t name itself, but very concretely produces precarity.

Ultimately, the question may not be purely geographical, but structural: building a career without being based in Paris is possible, provided one accepts that it will take more time, require more energy, and often rely on clear choices between visibility, economic viability, and quality of life.

“I think yes—there are profiles like Damien RK who build their careers by touring rural areas. Free party DJs as well, but without being professionals in the sense of being ‘financially autonomous’. But profiles like mine, aiming for clubs, warehouses, established festivals—no, it’s impossible. Unless DJing is my secondary activity and my job as a sound engineer is what actually pays the bills.”

— Scorch

Without being there physically? I’m not sure I fully get it, but if it’s about just doing production, I think anything is possible—though I imagine playing your tracks is still a big plus.

What they would say to a young DJ starting out outside Paris

When asked for advice, a shared line clearly emerges—and it’s reassuring. Do not make the capital an obligatory horizon or an overwhelming fantasy. Stay aligned with yourself, your values, your music. Do not give in to jealousy or passing trends. Accept that there is no single path to success.

Several encourage building locally, exploring scenes rather than chasing their supposed hierarchies. Staying local, within a passion-driven project, is just as legitimate. Building elsewhere often allows artists to arrive in Paris later with a project that is already solid—rather than the other way around.

Material and mental realities come up repeatedly. The importance of financial independence, the exhaustion linked to competition, the stress specific to the Île-de-France region. Nothing comes without work—but nothing is worth the cost of losing yourself along the way.

Lasting rather than breaking through

As the testimonies unfold, the question is no longer really whether one should go to Paris, but at what cost—and for what purpose. Behind the centralisation of opportunities lie complex realities: local scenes that are vibrant yet fragile; precarious economies; network dynamics that can be suffocating; and a widely shared mental fatigue.

What these artists express is not a uniform rejection of the capital, but a questioning of its status as a mandatory passage. Many are building elsewhere, differently—sometimes more slowly, but with greater meaning and coherence. Others patch together hybrid trajectories, choosing to work with geography rather than endure it.

Above all, this investigation reminds us of one simple thing. French electronic music cannot be reduced to the Paris ring road. It is shaped in mid-sized clubs, bars, community radios, squats, medium-sized cities, rural areas, queer scenes, bass, psy, house, techno, and unclassifiable spaces. It exists wherever people continue to create, programme, organise, and pass things on—often without recognition, sometimes without resources, but with undiminished conviction.

Perhaps the real question is not how to break through, but how to last. How to preserve desire, mental health, and artistic integrity within an ecosystem that rewards speed, visibility, and centralisation. Reading these voices from elsewhere, one certainty emerges: there is not one single scene, one single trajectory, one single definition of success. And this is very likely where the true strength of local scenes lies today.

Thank you to everyone who took the time to respond to this questionnaire and share their experiences—sometimes intimate, sometimes uncompromising: Tetris Owl, Basstrick, Lacrizomike 2000, Colleg, DJ Koyla, Shanix, Mysterykid, Cabale, Kirara, Snow, Le Caméléon, Bagrade, Axy_D, Lalahind, Tentakeur, Yerz, Solitary Shell, sCORCH, betises, BO MENG, ginger 808, harbinger, MagiKristy, and Bérengère.

Your words—your disagreements, your doubts as much as your certainties—draw a precious and necessary map of electronic music scenes outside Paris today. This investigation would have no meaning without your honesty, your clarity, and your commitment to making these scenes exist, questioning them, and defending them on a daily basis.