No products in the cart.

Hot Take: The One-Way Cultural Exchange of the Electronic Music Scene

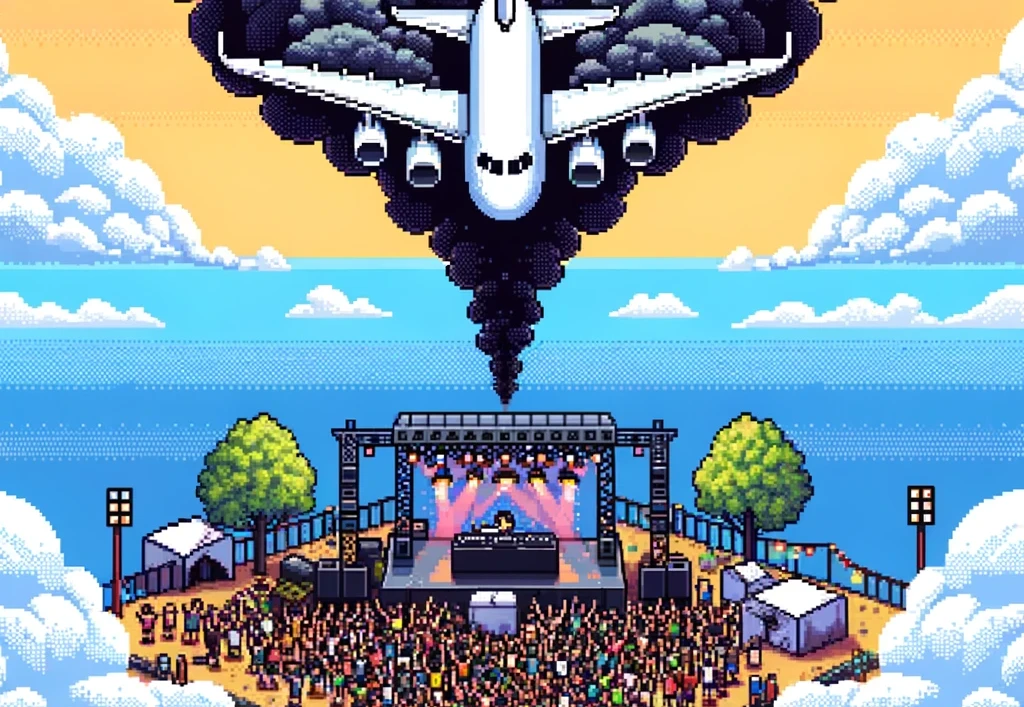

Since the global expansion of techno and house, Western lineups have broadened geographically. India, Colombia, Mexico, Brazil, Peru, “Asia”, South Africa. European and North American DJs are increasingly touring the Global South, describing these tours as transformative experiences and documenting them through spectacular imagery and spiritual narratives. The discourse is now familiar, built around ideas of openness, connection and cultural curiosity.

Yet this apparent expansion conceals a persistent imbalance. When looking at circulation in the opposite direction, movement slows down, sometimes to a complete stop. Artists from these scenes remain largely absent from European and North American lineups, or appear only marginally. They are rarely booked in the same time slots, under the same conditions, with the same resources as their Western counterparts. The exchange exists, but it is far from reciprocal.

Scenes from the Global South continue to be perceived as territories to be invested in rather than as creative hubs capable of exporting their artists on equal footing. They become contexts, backdrops, audiences, sometimes emerging markets, but rarely centres. DJs play there, extract energy, build international narratives, without this translating into sustained structural recognition for those who produce the music locally, day after day.

The 2019 Dekmantel controversy crystallised this unease. That year, the Amsterdam festival announced a lineup of more than 100 artists without including a single DJ based in Latin America, despite running multiple editions and collaborations across the region. The response from Valesuchi, a Chilean artist based in Brazil, did not point to a simple oversight but to a deeper issue of perspective. How can we continue to speak of cultural exchange when recognition stops at European borders, and relationships built elsewhere fail to be reflected in central flagship events?

This imbalance is not only geographical. It reflects a broader logic of centralisation and hierarchical value systems that also operate within Western countries themselves. The reactions to our investigation into regional DJs, who remain largely underrepresented in Parisian lineups despite vibrant and innovative local scenes, point to the same issue. Once again, circulation is restricted by centres of power, visibility and legitimacy that reproduce identical mechanisms of exclusion, simply on a different scale.

In all these cases, booking an artist already perceived as “central” is considered a safe choice. The audience is assumed to be there, algorithms provide reassurance and the narrative is familiar. By contrast, inviting a DJ from a scene labelled as peripheral, whether geographically or symbolically, requires a real effort. It means stepping outside automatisms, accepting artistic and sometimes pedagogical risk, and above all questioning the implicit criteria that define legitimacy.

This is not about blaming DJs who tour internationally, nor about denying the reality of human and artistic exchanges that do take place on the ground. The issue is structural. It concerns programmers, festivals, agencies and all those who organise artist circulation and decide what deserves to be seen, heard and exported.

The question therefore remains the same, whether we are talking about the Global South or local scenes far from cultural capitals. At what point do we truly speak of exchange? When artists can circulate as freely as the audiences they play for. When their music stops being a backdrop (hello Tulum) and becomes a point of reference. When curiosity no longer operates in only one direction.

Without this shift, the cultural globalisation claimed by the electronic music scene will continue to resemble a form of soft colonisation, reproducing the very centre periphery logics this scene so often claims to have left behind.