No products in the cart.

“When Night Falls” — Inside Fabrice Catérini’s Photobook

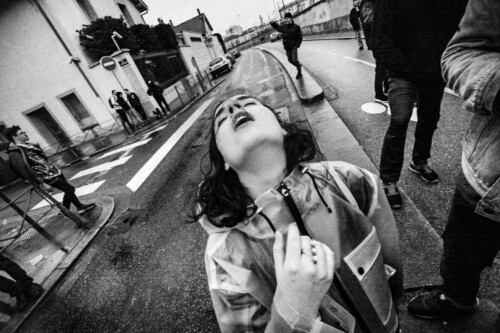

Reading When Night Falls means accepting to enter a territory where darkness is never merely the absence of light. For Fabrice Catérini, the night becomes a passage, a crucible, a space where masks fall and inner truths surface. For seven years, he photographed intimacy as much as celebration, faces as much as his own ghosts, composing a visual narrative that oscillates between collapse, rebirth, and elevation.

In this interview, he looks back at the genesis of the book, his relationship to reality, to electronic scenes, to ethics, and to the human fragility that inhabits each image.

1/The title says “When Night Falls”, but your text also evokes the returning dawn. Is this book a crossing or a liberation?

Both. This book is an odyssey, a passage; it is built through oscillation, not a straight line, just like a life path that is often winding. *When Night Falls* opens and closes with a palindrome attributed to Virgil — who, in *The Divine Comedy*, guided Dante from hell to paradise — referring to moths drawn to the flame and consumed by it. The book wasn’t born from a concept. It was born from a fall, or rather a slide — a slow tipping into the night, experienced as revealing, as a space of cathartic learning. This is also why the title and the intimate river-like narrative appear in the middle of the book, not at the beginning. When you realise you have truly plunged into the heart of things, the night has already exerted its pull, and you gravitate more or less closely around its orbit. Through my personal experience and an intimate prism, it is a book about surrender, about celebration and night in the broad sense, yes, but also about wounds, traumas, solitude, and the reasons people seek refuge there. We enter the night because we carry wounds and burns we haven’t managed to extinguish: grief, addiction, loss, betrayal, illness. This rose and this lifeline are witnesses to that.

2/You describe a seven-year initiatory journey. How did the night transform you, humanly and artistically?

Those seven years taught me that one must accept to look deeply within, without filters, but with tenderness. The night teaches us to move even more toward others. In this image, for example, the man is wearing my beret — it’s a self-portrait, but made by two. In the night, each person can build a character, from the Latin *personae*, meaning mask. A mask different from the one worn in daytime. And when it falls, it cuts both ways: it sometimes hurts, yes, but it is also where beauty and fury can rise and fully unfold. The night offers a lesson in impermanence; it is conducive to and a driver of elevation, a full spectrum of possibilities. As an artist, the project slowly imposed itself on me over time, echoing David Lynch’s idea: “Ideas are like fish, and you don’t make the fish, you catch it.” The night helped me assert, sharpen, and refine my voice over time, like a craftsman who crafts weapons to fight but above all tools to build — in the crucible of experience.

3/Which image marked you the most in this shift?

There is no single icon or image that could summarise everything — impossible. I am not a “trigger-happy” photographer, but since the book mixes personal life, commissioned images, and multiple experiments, night and day… We started with more than 50,000 images, then 5,000, and finally about a hundred in the book. Sacrifices were inevitable. Each image is therefore a marker. And sometimes, the images that did not find a place in the book — but can be sensed in the text — make meaning as well. The challenge was to find a whole that becomes more than the sum of its parts.

4/Your text says photography helped you “come out of the dark.” Was this work therapeutic?

Yes, I’m convinced it was, and I think it is a work that can lead people — not only night owls — to question their relationship to the world and others, their zones of shadow and light, their traumas. It is a work with dreamlike appearances but grounded in truth; we start from the intimate to reach the universal. It is a mirror held up to the reader, like the book’s cover in which the reader is reflected. In *When Night Falls*, there is only one image with a DJ, which is quite significant: I speak less about the “system” of nightlife — although it is present in the background — than about the individuals who inhabit it. It is also a gift for owls and night birds, for this community of wounded souls who will make the work their own.

5/Techno has always been tied to liberation, utopia, sometimes struggle. Did you feel that while photographing nightlife?

Yes of course, for me it is the DNA of free party culture — the invocation of otherness, another possible world, freedom of thought, non-judgement, and egalitarian experiences. The night is an eminently political space, and partying is an act of rebellion. Historically, and still today, it is a place of emancipation where everyone can “live without witnesses,” according to philosopher Michael Foessel’s accurate expression. There is something deeply touching in this desire for forgetting and belonging. Some after-party promises fade at dawn, but the breath remains.

6/Do you ever censor yourself (for social media or even for this book)?

Yes, it has happened, for instance when I learned information about the people photographed. It is more a matter of common sense and humanity than censorship. I am not a communicator; I come from a photojournalistic background, so if I need to show something to denounce it, I do — but never at the expense of others, especially not someone vulnerable. I am certainly not here to steal anything. If someone is in difficulty and I am the only one who can help, I put my camera aside — that’s basic. This stance also comes from my experience in documentary and humanitarian fields: dignity comes before publication; accuracy comes before performance.

7/How do you handle consent when shooting nightlife?

Consent is a process, and above all, it is not fixed. If, for example, I capture a moment of intimacy, I go to the people, show them, explain my approach, and, if possible, send the image immediately when I work digitally, or I take their contact and make sure it’s okay for this or that use — sometimes years later. Photojournalists like Eli Reed or Stanley Greene passed on to me a practice of “concerned” photography with a deep sense of ethics. Being a photographer is not simply about producing beautiful images. It is a dialogue, and the camera is a powerful tool for change, not a decorative necklace.

8/Electronic scenes are changing a lot: gentrification, mainstreaming, fading underground codes… How does your artistic eye capture these shifts?

By avoiding folklore as much as possible, and smoothed-out storytelling. By staying curious, accepting roughness, and continuing to question myself. I remain hopeful and we shouldn’t be too defeatist; there will always be islands of resistance for those who want to step off the beaten path and avoid a “monoform.” There are still people of goodwill. But we must be realistic: it is becoming increasingly difficult for independent structures — just look at the disappearance of many small clubs, and the rise of extreme behaviours. A whole part of the scene is dying.

The broader ecosystem is becoming more polarised every day, between free-parties and raves increasingly criminalised, and on the other side, a cash machine running wild and benefiting a minority.

Technocapitalism is exploding, there is an alarming concentration of power, everything is sold as spectacle… Even small structures proclaim themselves underground and practice opportunistic “freewashing.” It is often completely hypocritical, but it’s trendy and profitable, offering the transgressive thrill of a warehouse in a surprise bag. Some renowned clubs promote inclusivity, solidarity and equity, while behind the scenes everything is largely pyramidal — and many stay silent, otherwise you get cancelled.

It is not surprising: it is the visible symptom of a consumerist society structured around attention, where swipe culture becomes systemic. DJs become influencers and vice versa, with the booth as a stage. Drops fall as fast as decrees, and videographers film as if on a boat in a storm, trembling at terminal stage.

9/What are the biggest difficulties nightlife photographers face, in your opinion?

Let’s be honest: first of all, precariousness. It’s similar to the gap between local DJs, indirectly exploited by those considered bankable and monetisable. There is a clear abuse of power and dominant position from certain organisations or well-established clubs that pay far below minimum wage, even when the work is demanding. Copyright is widely violated. Nightlife is a place of freedom, but also a privileged space for prowlers of all kinds who can act with impunity, far from daylight. The photographer or videographer is too often there to feed the ego machine of promoters, DJs, and the spectacle society in general. Under economic pressure or out of intellectual laziness, creators fall into ease. The uniformisation of the gaze, by hiding certain aspects of the night, threatens the medium’s meaning and perpetuates a postcard image. Keeping our “eyes wide shut” is becoming the norm.

Yes, nightlife is unity, beauty, communion — but it is also distress, addiction, escape, death, violence. We must accept this in public debate and raise awareness: a harm-reduction booth is the baseline, not a goal — and even that is under threat.

Unfortunately, having an author’s voice — independent and critical — showing aspects that aren’t merely “romantic” is not valued at all, and (self-)censorship often does the job: at night, all cats are grey.

A small anecdote: I recently had to hide my camera in my underwear to document a major French festival. My accreditation was refused, even when requested by a well-established press outlet. Sponsored content disguised as reporting is becoming the norm. Media and magazines are timid and produce smooth content: boldness, duty to inform, and genuine risk-taking are becoming very rare — and it’s a shame, almost surreal, like that fractured eye.

Biography:

Fabrice Catérini is a visual artist and filmmaker born in the Lyon region. After studying cinema, he co-founded the Inediz agency in 2012 and worked on long-form documentary narratives: migration in Greece, a neglected tropical disease in Nigeria, or the anti-nuclear movement in France, before shifting his practice toward a more personal and experimental approach. Today, his work explores the boundaries between day and night, reality and fantasy, the visible and the invisible. It unfolds through transversal projects: immersion in the nocturnal world of electro-techno scenes, exploration of reflections and illusions on Google Street View, or the reactivation of historical photographic processes to question our relationship to images.

https://www.instagram.com/fabcaterini/

Book Overview:

The story of this book begins where daylight ends: when night falls. It is the story of a headlong flight, far from the diurnal world and its harsh, singular, zenithal light. When day turns to night, sources of light multiply: celestial bodies and artificial lights transfigure space and time. He plunges into this troubled water, which first welcomes him and then calls him, absorbed by this dark energy that moves through him and transforms him. He does not know it yet, and yet he is embarking on a journey that will last seven years. A journey to the end of the night, intense and initiatory, during which he will search for love in all the noises of the world, tracking fragments of reality in the realm of dreams and masks. But night, full of promises, always gives way to dawn. And in the end, it is photography itself — the art of writing with light — that will allow him to come out of the dark.

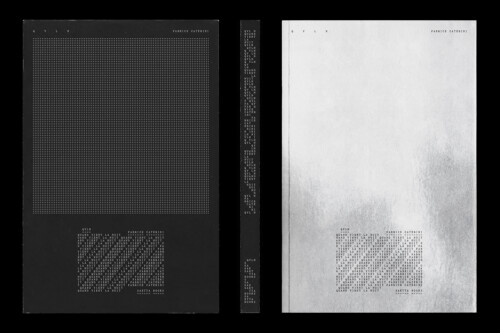

- 168 pages, sewn binding

- Black perforated jacket

- Softcover with mirror lamination

- 200 × 300 mm

- 102 black-and-white photographs

- Bilingual French–English book

Order the book:

https://www.saettabooks.com/product/quand-vient-la-nuit